Algorithm And Maine

A tale of two media

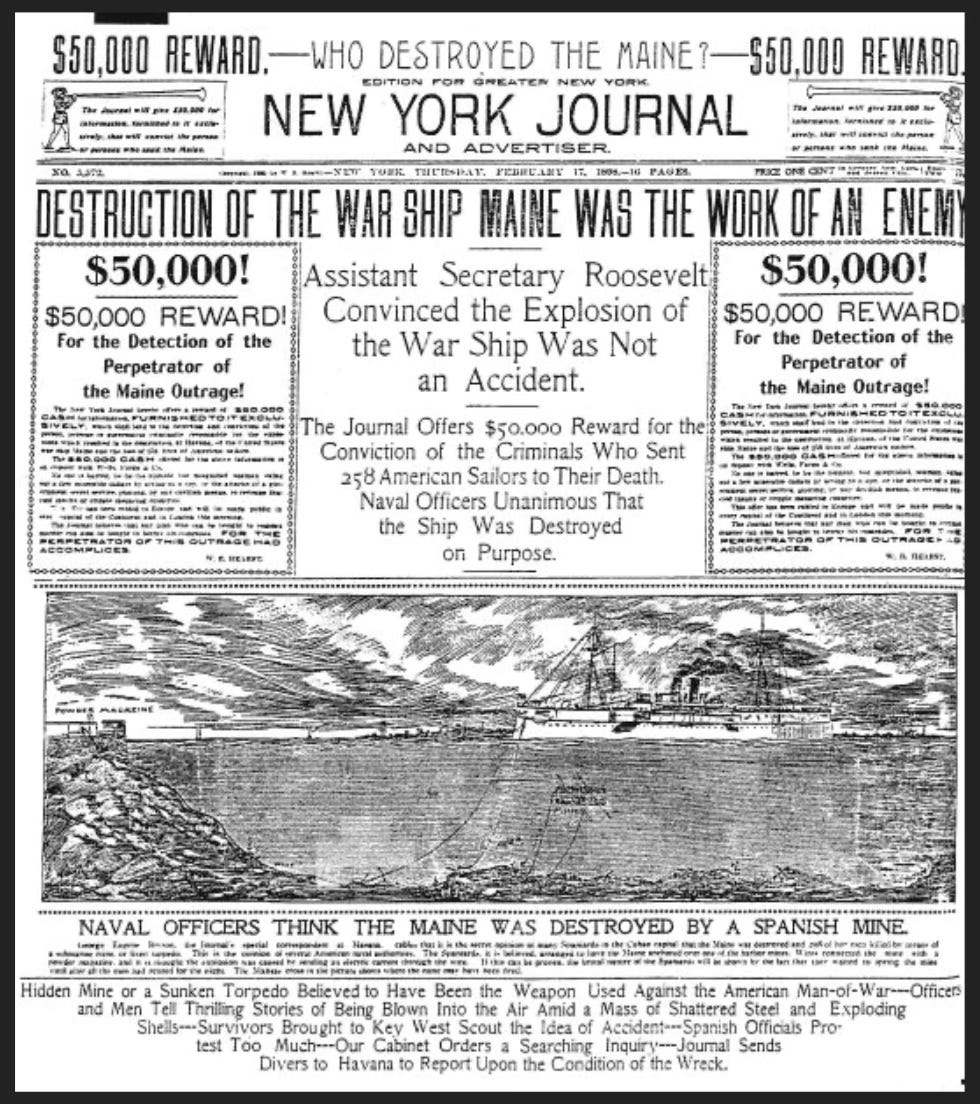

In January 1898, the USS Maine sailed into Havana Harbor on what was supposed to be a diplomatic mission –partly to smooth things over with Spanish authorities, partly to protect Americans caught up in recent riots in Cuba. One month later, the ship exploded killing 260 sailors.

Within hours of the incident, two rival newspapers run by two media titans – determined to best one another – blamed Spain. And, devoid of evidence, published fabricated diagrams and stories under the banner of inflammatory headlines. "Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain!" quickly evolved into a rallying cry that whipped the public into a frenzy. By April, we were at war.

More than a century later, we are watching the same sort of playbook unfold, just faster and louder. Grab attention at any cost, confirm what people already believe and worry about accuracy later. At the turn of the 19th century, it was Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst battling for newspaper sales with sensational headlines about the Spanish-American War. Today, the titans are tech overlords vying for eyeballs across their social media platforms with content designed to make us angry, afraid and addicted to scrolling. The format is different. The objective, not so much.

Meanwhile, the main stream media, which has for decades included 24-hour cable news networks that may – in hindsight – come to be seen as a catalyst for a new era of Yellow Journalism, has lost almost all credibility with the American public who, instead, are glued to said social media platforms where a combination of self-appointed citizen journalists – from public officials and business leaders to demagogues and pretty much anybody with an iPhone – vie for their attention. Without any obligation (literally, Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934 shields these platforms from being obligated) whatsoever to the facts.1

So, what exactly are ethics these days in terms of journalism? And how are they relevant in an era where only a handful of outlets read by fewer and fewer people strive to adhere to them?

I found myself mulling these questions over earlier this week as I sat at a table with three strangers, debating whether to publish a photo of a dying soldier. It was not exactly dinner conversation, but rather an assignment at an "Ethics Palooza," an evening organized by a local news non-profit (Foothills Forum) that asked groups of people to consider ethical dilemmas often faced by news editors. And while the format was simple – small groups of four to five people per table, each with a working journalist (I assumed this role at my table) to guide the discussion – the discussion proved anything but.

Social Media As Evidence

The first scenario bumped right up against social media. A high school student dies by suicide using her father's gun. No suicide note, but her Instagram account is filled with allegations of years of physical and psychological abuse by her father. Law enforcement, social services and school counselors all say they have no reports of abuse. The grieving father asks for privacy in the wake of the tragedy, and to leave his family alone.

The question for the editor of a hypothetical local paper: Do you report on the Instagram posts even though they are unverified or do you ignore them even though they are already circulating through the community?

My table was split. Some argued that ignoring the allegations when they were already spreading would damage the paper's credibility, leaving readers to wonder why the paper was not addressing the elephant in the room. Others worried about amplifying unsubstantiated claims against a grieving parent, especially given the irreversible damage false accusations could cause.

Though no one framed it this way, social media was foisting an ethical dilemma upon all of us. Namely that the community would be suspicious if the allegations were not at least acknowledged, despite the fact no one had confirmed the death was indeed a suicide or that the potential damage of accusing the father of abuse merited further investigation. While an imaginary editor and reporter debated the ethics of publishing unverified allegations, it is probably safe to assume those same allegations were spreading unchecked across social media platforms with no editorial oversight, no fact-checking and no consideration of harm. In other words, the very allegations an editor or reporter was wrestling with as “news” had likely already been shared thousands of times by people who never paused to consider their veracity or impact.

Public And Private

The second scenario proved every bit as sticky. A local elected official gets a DUI, with police reports showing he was so intoxicated he could not remember his address. While researching a feature on Alcoholics Anonymous, a reporter was told by two recovering alcoholics that the official not only regularly attended their meetings, but had spoken about his arrest and alcohol struggles. When contacted for verification about his participation in AA, considering the arrest, the official says "no comment."

For participating members, AA’s anonymity is sacrosanct – and widely considered essential to the program's effectiveness and many people's willingness to seek help. But there is also the issue of an elected official whose alcoholism might be relevant to voters, especially when he has maintained publicly that he is a moderate drinker.

Some at my table felt the public’s right to know about an elected official's character outweighed AA's code of anonymity. Others argued breaking the anonymity could discourage others from seeking help and undermine trust in a program that has been foundational to the recovery of tens of millions of people.

In the end, there was consensus around reporting the DUI as a matter of public record and framing the issue of alcohol abuse among elected officials as a broader issue without specifically mentioning AA. I should add that I posed the question to a highly respected newspaper editor in private at the end of the evening who said he would absolutely have published the allegations about being in AA (for the record, so would I had I been the editor), that a public official is not entitled to the same protections as a private citizen.

But here again, social media – which we did not discuss – would likely have already complicated the decision. While an editor and his team debated the ethics internally, information about the official being in AA was probably already circulating in private Facebook groups and local chat threads. Any editorial restraint that might protect AA's principles would be happening in a parallel universe, adjacent to a digital free-for-all where no such protections exist. Sometimes what you do not publish is as important as what you do – but what weight does that principle carry when others are publishing everything without any principles at all?

Bearing Witness

The third scenario was equally lively: A local photojournalist is assigned to accompany a peacekeeping unit from the community to a war zone and captures the moment one of them is shot and killed. The dying soldier's face is clearly visible, as are the anguished expressions of the others trying to save him. It is close to deadline and the families have all been notified. Do you publish the photo as a testament to the dangers of war or do you hold it out of respect for the family and community? Or, do you seek the family’s permission even if it means missing the deadline?

The debate got heated. Some argued the photo would powerfully illustrate the human cost of the mission in a way that words could not. Others felt showing someone's dying moments, even for noble purposes, crossed a line of basic human decency. Some believed consent from the family should be sought; others said seeking family approval for editorial decisions would compromise journalistic independence. What few considered is that the job of a journalist (and a photojournalist in particular) is to bear witness. And how powerful an image can be in conveying a story – my mind immediately went to a singular image of a young girl running from a napalm attack in Vietnam.

The irony was not lost on me that while we debated the ethics of our single image, graphic (often gruesome) photos and videos of shootings from our schools and churches and community gatherings were circulating on social media without consent, notification or consideration of harm. The public wants immediate, unfiltered reality, and can be quick to criticise traditional outlets for delays or omissions.

Children flee a napalm attack in Trảng Bàng on June 8, 1972. Left to right: Phan Thanh Tam, who lost an eye, Phan Thanh Phouc, Kim Phuc, and Kim's cousins Ho Van Bon, and Ho Thi Ting. The "Napalm Girl" photograph galvanized an anti-war movement in the United States.

Associated Press/AP

An Age Of Disinformation

In the end, what struck me most about the evening was not a particular conclusion reached, but the contrast between the careful deliberation happening among a group of community members – people sitting with one another and having to be accountable to one another – and the information chaos happening across widely used social media platforms. While we wrestled with whether to publish unverified allegations, those same allegations were likely spreading unchecked across social platforms. While we debated the dignity of publishing images of a member of the community killed in action, graphic content from killings closer to home (often of school children) were being shared without consideration. While we considered the impact of “outing” someone in an anonymous forum, stories about people’s personal struggles were being weaponized in comment threads everywhere.

All of which creates a seemingly insurmountable dilemma for traditional media. The public often criticizes mainstream outlets for being too slow, too cautious, too “conciliatory”. Rather than crediting them with being responsible, deliberative or – dare I say – ethical. While social media users are empowered to fire off posts in real-time (some are even rewarded for it), editors are obligated to ask hard questions: Is this verified? Could this cause harm? What is our responsibility to the public?

As I drove home, I was heartened to have seen how we consume news differently when we understand the ethical wrestling matches happening behind every story. But the reality is, that is not our reality. Instead, we live in an age where anyone can publish anything instantly, where verification is optional, harm is an afterthought and consequences for getting it wrong are few-and-far between. Against this backdrop, traditional journalism seems antiquated – or even incompetent. But when done properly, better serves the public.

Afterall, the First Amendment – in my opinion – is not there to protect press freedom so that journalists can be stenographers for bad-faith actors, but to ensure access to accurate information so that citizens can make informed decisions.

If the coverage of the sinking of the USS Maine taught us about the harms of sensationalist “Yellow Journalism,” so much so that it eventually led (some 40 years later) to the Hutchins Commission and a formal inquiry into the proper function of the media in a modern democracy, then forty years or so on from the advent of 24-hour news as entertainment, might it be time for another reckoning?

1 Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934, enacted as part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, provides limited federal immunity to providers and users of interactive computer services. The statute generally precludes providers and users from being held liable—that is, legally responsible—for information provided by another person, but does not prevent them from being held legally responsible for information that they have developed or for activities unrelated to third-party content. Courts have interpreted Section 230 to foreclose a wide variety of lawsuits and to preempt laws that would make providers and users liable for third-party content. For example, the law has been applied to protect online service providers like social media companies from lawsuits based on their decisions to transmit or take down user-generated content.

This was thought provoking, I know it because I have so many questions. How does traditional media even begin to reconcile what seems to be like you said such an insurmountable problem. The three scenarios in your workshop presented serious moral and ethical implications, and they highlighted the importance of social responsibility in the age of social media. I enjoyed your piece. 🙏🏼

On a side note; the amount of damage that the words FAKE NEWS! has done to the institution of the fourth estate has been absolutely catastrophic.

Thank-you for this. It's a necessary & timely look in the mirror that resonates now for many reasons. What clicked in it for me is the parallel with questions that those in the humanitarian profession have also grappled with for decades surrounding the use of graphic images to 'sell' their fundraising & advocacy efforts. Some 30 years ago the profession came up with a now-widely adopted 'Code of Conduct' that includes, among other norms of behavior, this undertaking:

"In our information, publicity and advertising activities, we shall recognise disaster victims as dignified humans, not hopeless objects. Respect for the disaster victim as an equal partner in action should never be lost. In our public information we shall portray an objective image of the disaster situation where the capacities and aspirations of disaster victims are highlighted, and not just their vulnerabilities and fears. While we will cooperate with the media in order to enhance public response, we will not allow external or internal demands for publicity to take precedence over the principle of maximising overall relief assistance. We will avoid competing with other disaster response agencies for media coverage in situations where such coverage may be to the detriment of the service provided to the beneficiaries or to the security of our staff or the beneficiaries."

That's the ideal, but it seems to be eroding fast. We're falling back on our old ways. The Code of Conduct is here if you're interested:

https://www.ifrc.org/document/code-conduct-international-red-cross-and-red-crescent-movement-and-ngos-disaster-relief